In Mirco Magnani’s work, philosophy, literature, and sound are never separate realms. From his early days with Minox in the Italian new wave of the 1980s to his more recent explorations in Berlin, Magnani has pursued music as a field where ideas become audible and transformation takes place. Whether setting Nietzsche’s “Also sprach Zarathustra” to sound, working with alchemical concepts in the “Magnum Opus Collectio Series,” or reinterpreting myth through collaborative projects like Lumiraum, his practice continuously seeks thresholds where text, image, and sound overlap. The founding of his label Undogmatisch further reflects this commitment: not as a commercial enterprise, but as a space for experimentation and dialogue. Together with visual artist Valentina Bardazzi and long-term collaborators such as Steven Brown, Magnani continues to expand his range across formats and disciplines. His trajectory, shaped by both loss and renewal, resonates with a rare intensity: deeply rooted in past experiences, yet always moving toward new constellations of meaning.

In Mirco Magnani’s work, philosophy, literature, and sound are never separate realms. From his early days with Minox in the Italian new wave of the 1980s to his more recent explorations in Berlin, Magnani has pursued music as a field where ideas become audible and transformation takes place. Whether setting Nietzsche’s “Also sprach Zarathustra” to sound, working with alchemical concepts in the “Magnum Opus Collectio Series,” or reinterpreting myth through collaborative projects like Lumiraum, his practice continuously seeks thresholds where text, image, and sound overlap. The founding of his label Undogmatisch further reflects this commitment: not as a commercial enterprise, but as a space for experimentation and dialogue. Together with visual artist Valentina Bardazzi and long-term collaborators such as Steven Brown, Magnani continues to expand his range across formats and disciplines. His trajectory, shaped by both loss and renewal, resonates with a rare intensity: deeply rooted in past experiences, yet always moving toward new constellations of meaning.

Your most recent album is “Zarathustra – Der Große Mittag,” produced together with Steven Brown, Sainkho Namtchylak, Nikolas Klau, and Paganland, based on the text by Friedrich Nietzsche. You’ve probably known the text for a long time – what inspired you to create your own work based on it?

Yes, I’ve been familiar with “Also sprach Zarathustra” by Nietzsche for a long time, but I see it as an extremely complex text. Each time I return to it, I find new meanings, new doubts, new contradictions. After many years, I picked it up again and suddenly, another door opened—bringing that same mix of excitement, frustration, and fascination in trying to grasp what still hides behind those words.

That’s where the idea for a new album came from. I wanted to continue the path I started with “Madame E.”: using a literary text from the past as a libretto, working with a specific compositional and performative approach, and involving the same artists like Stellan Veloce Andrea De Witt and Valentina Bardazzi, along with Yakovlev and others invited to interpret Nietzsche’s voice.

The underlying idea is to create a trilogy. In the future, I’d like to develop this concept into a third album, following roughly the same creative process.

The album interweaves Nietzsche’s text in four languages with sound art – how did you come up with the idea of interpreting Nietzsche’s myth multilingually (and thus cross-culturally)?

After composing the music for the album, I began thinking about how to approach the interpretation of the text. The first step was deciding who to include. One of the main criteria was to involve artists with a certain artistic maturity—not only to give voice to an ideal Zarathustra, but also to reflect the various facets and contradictions of a historical figure reimagined by Nietzsche.

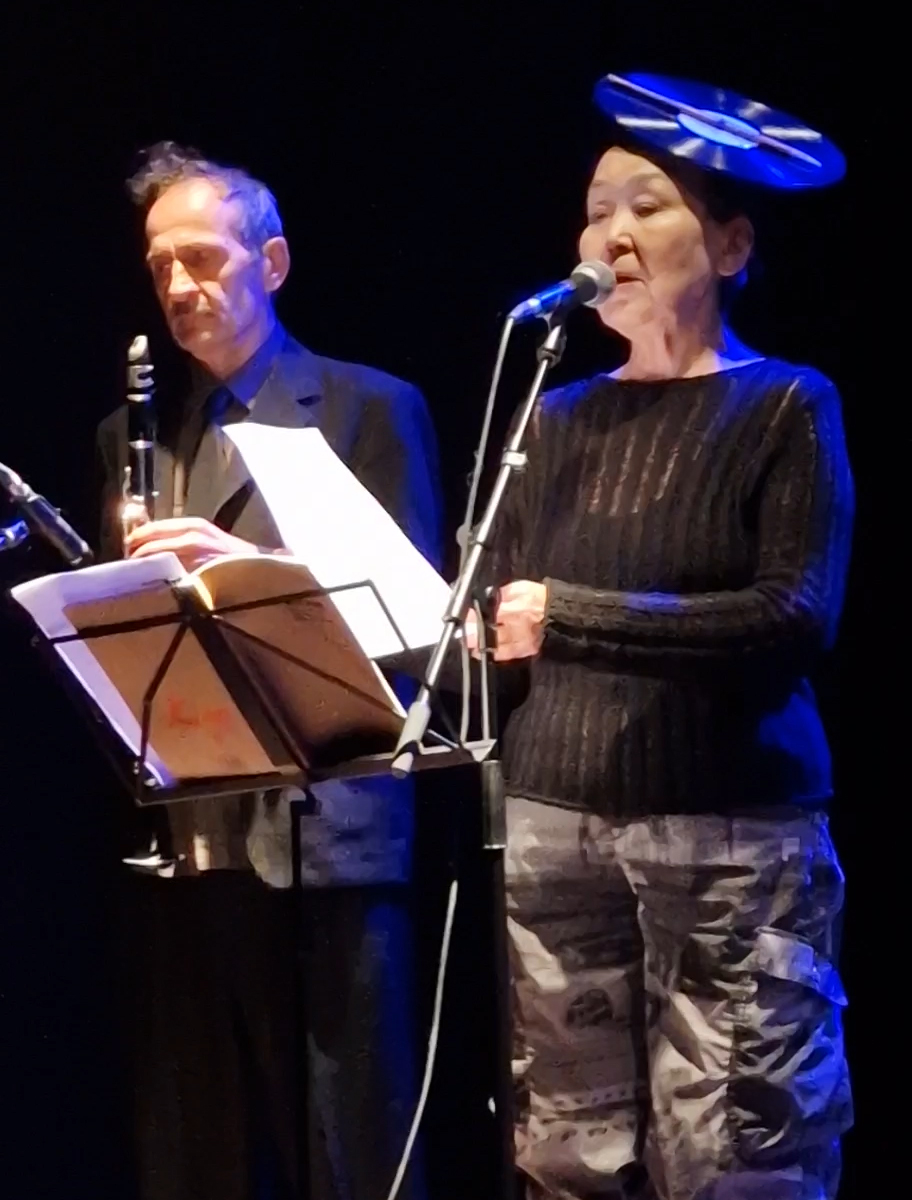

The first artist I involved was Steven Brown, who naturally embodied the kind of presence I was looking for. His contribution was essential in initiating this phase—not only vocally, but also musically, as he performed alto sax and organ parts.

From there, I selected other artists who could reflect additional dimensions of Zarathustra/Nietzsche. The choice was based not only on their artistic and human depth, but also on language and cultural context: Persian, German, Russian, and English. I ended up working with long-time collaborators like Steven Brown and Nikolas Klau, as well as new voices such as Sainkho Namtchylak and Paganland.

How has your approach to integrating text (e.g., Nietzsche, Bataille) changed over the years?

I wouldn’t say the methodology of integrating text and music has changed, but rather the need to work with two very different types of texts: Bataille’s is a short story, while Nietzsche’s is a complex work divided into four distinct parts. Yet both were approached in a new and original way, aiming for strong impact and a break from conventional norms—perhaps still difficult to fully accept today, due to the themes they explore: eroticism, religiosity, death, spirituality, evolution, nature, the absolute, and more.

How has your move from Pistoia, Toscana, to Berlin years ago affected your aesthetic and collaborative concepts? What does this mean specifically for you as an artist and label founder? Both places have active, but probably very different, musician and artist communities.

When I moved to Berlin, I had already long felt the need to leave Pistoia, a small provincial town in Tuscany close to Florence where I had co-founded several bands and a couple of independent labels. In retrospect, I realize that the absence of a strong artistic presence — like the one in a city such as Berlin — actually pushed and inspired me to do what I did, as if I were chasing an elusive, unreachable, utopian dream. This necessity drove me to seek collaborations with international artists to compensate for that lack and, at the same time, to help build a small local scene and broaden the boundaries of the Tuscan and Italian music landscape of the 1980s.

Der

Der

Moving to Berlin in 2009, after many years of work in Italy with independent labels (I.D. Lacerba, Suite Inc.) and bands (Minox, 4D Killer, Technophonic Chamber Orchestra), was a turning point. I was able to deepen my experiences and collaborations within a vibrant international scene. Still, it came with new challenges: before, the difficulty lay in working within an almost non-existent scene — now, it was about standing out in a large, fragmented, and highly competitive environment constantly chasing the next new thing.

What motivated you to found your own label, Undogmatisch? Do you see it as a continuation of previous activities or more as a new beginning?

Founding an unofficial label like Undogmatisch was a natural extension of my artistic journey. Undogmatisch initially started as an event series hosting simultaneous AV live performances, DJ sets, and multidisciplinary exhibitions. It later evolved into a label focused on self-production, drawing on the skills and experience I had gained through my earlier work with I.D. Lacerba and Suite Inc.

In this sense, it was both a continuation and a new beginning. Running this project without commercial expectations proved valuable — especially given the drastically different historical context compared to the 1980s and ’90s, when one could still hope — and sometimes manage — to turn such an endeavor into a full-time profession.

Valentina Bardazzi is not only a co-owner of Undogmatisch, but also a visual artist present in many of your projects. How does the collaboration between music and visual art work?

Valentina is continuously informed and follows the entire production process from start to finish, allowing her to maintain a comprehensive and consistent vision of each project. In addition to being a visual artist, she has a strong musical background, which enables her to fully grasp concepts and content and translate them into compelling visual interpretations.

You’ve been working with various media for decades, from music to installations to video art; literature also plays a recurring role. How does your artistic approach change in the transition between sound, word, and image?

I would say that these three media — music, installations, and video art — evolve in parallel and influence one another. Thanks to this exchange, the creative approach doesn’t change but rather expands and regenerates itself. Sometimes an idea originates from a literary text and then unfolds into the other forms; other times, it may begin with a sound or a visual element. There is no single path.  Was fasziniert dich an der Schnittstelle von Philosophie, Mythos und Klang – und welche Rolle spielt Spiritualität?

Was fasziniert dich an der Schnittstelle von Philosophie, Mythos und Klang – und welche Rolle spielt Spiritualität?

Aside from the differences, what fascinates you about the intersection of philosophy, myth, and sound—and what role does spirituality play in your work?

Philosophy, myth, and sound share a common denominator: they all seek to transcend the physicality of the world, offering a different perspective on reality and helping us in our process of evolution. I have become increasingly aware of how important spirituality is in my work; it certainly always has been, but over time I have grown more certain and conscious of it.

The “Opus Magnum Collectio Series,” which you curated and edited, is conceived as a multi-part work that encompasses electroacoustic composition, philosophy, and ritual structure. What was the starting point or driving idea behind this series for you?

The entire concept behind the “Magnum Opus Collectio Series” was conceived during the pandemic period, which strongly motivated me to structure this series based on my interests and knowledge of alchemical matter. During that time, a sort of transmutation occurred within human beings: a moment when humanity revealed its true nature, when we all felt vulnerable but gradually became increasingly aware.

The significant contribution of all the artists involved — some I already knew, others I invited because I appreciated their work — gave me great joy and strength to carry on despite the difficulties and uncertainties of that time. I take this opportunity to thank them all once again!

The concepts and symbols of alchemy—transformation, sublimation, dissolve and coagulate—permeate many levels of the series. What does alchemy mean to you as an artist and personally?

I do not consider myself an alchemist, but I am drawn to the ideals underlying alchemical science. I believe that certain concepts can definitely help us understand reality and ensure that our behavior aligns with knowledge and consciousness. There is a great difference between Knowing and Being: we don’t always actualize or embody what we know. Instead, we should strive to become and be what we have learned and will learn over time.

To what extent is your approach to composition and sonic texture itself an “alchemical” process—a kind of inner laboratory in which elements gain new meaning through friction, transformation, or even destruction?

I believe that over the years I have acquired individual knowledge connected to experience, meditation, and spirituality, as well as an objective understanding of how a process leads to a solution or transformation. I am trying to become increasingly skilled at transmuting a feeling into a sequence of notes or sounds, transforming it into a form that is more objective and less subjective.

The series follows the alchemical phases (Nigredo, Albedo, Rubedo)—to what extent was Carl Gustav Jung’s concept of individuation a source of inspiration?

I’m not very familiar with the full work and writings of C.G. Jung, but I have studied some of his key concepts, such as the individuation process. This has been a major source of inspiration in defining the concept of the series.

The individuation process is a unique and unrepeatable psychic journey that leads each individual to reconcile their ego with the Self. In other words, it is a progressive integration and unification of all shadows and complexes that shape the personality within oneself.

To what extent do the contributions of the other musicians in the series reflect your own vision of transformation through sound?

In the three releases of the “Magnum Opus Collectio Series,” I invited a diverse group of artists I admire, chosen from various musical subgenres and many different countries, all dedicated to experimentation. I gave them full freedom to interpret the alchemical theme of the three phases in their own way and style, and each, more or less, captured the essence of what I intended to communicate. I am very satisfied with the artistic quality and depth of this collective project and hope to repeat this experience in the future. The artists involved come from Italy, China, Iran, the Netherlands, Spain, Greece, Cyprus, Mexico, Denmark, Germany, Sweden, Japan, Malta, and Poland, but most live in Berlin or are somehow connected to Undogmatisch.

You have repeatedly worked with Lukasz Trzcinski on the joint project Lumiraum. What significance does the connection between mythological creation stories and sound as a form of expression have there?

The period during which we recorded “Lumiraum” and “Lumiraum Appendix” was an important moment when Lukasz’s desire to collaborate coincided with my need to engage with other artists in composing new pieces freely, without constraints, allowing room for improvisation. In this case, the approach was meditative and connected to the mythological concept of cosmogony as seen in various world cultures.

What role does the symbol of light (lumen) play in the musical design of your pieces?

Light, as a contrast to darkness, is part of an active/passive dualism necessary to create a third neutral force, an indivisible reality. Light is neither more nor less important than darkness, but in a way, it is the spark that ignited something already ready to be changed and transformed. A procreative spark that allows us to see, distinguish horizons and limits, consciousness and awareness.

I’d like to ask a few questions about your early work from the 80s and 90s, which is somewhat less well-known to many in German-speaking countries. What can you tell us about your first musical projects, and how strongly do you still feel connected to them today?

My early works influenced me deeply; it was a wonderful period to which I still feel very connected. It was the 1980s, and meeting the members of Minox, with whom I shared musical knowledge and influences, was certainly an important phase of growth and exchange. The first recording sessions, the first concerts, and the initial international collaborations took place during a time when independent labels were, in some way, changing the rules of the music industry.

Your band Minox was (probably, because I only know parts of the scene) an exceptional phenomenon in Italian New Wave back then, also because their sound on their debut album “Lazare” also had a chamber music aspect, with an instrumentation that included clarinet, piano, double bass, and trumpet. Was this a conscious counterposition to common scene standards, or did it arise more “automatically” from the logic of the songs and the instrumentation of you and your guest musicians?

The new wave/post-punk phenomenon attracted us a lot at the time, but within that scene, various subgenres had developed, showing us multiple facets and allowing us to give our own personal interpretation of the movement. In Minox, we were five members, each with our own background: five minds with different peculiarities. We didn’t want to tie ourselves too closely to any one movement or scene. At that time, Florence was often called the capital of Italian new wave, but somehow we didn’t feel part of that scene, which was closer to the Anglo-Saxon new wave, and we were aware of that.

The clarinet still plays a role in your musical work today. Would you describe it as a leitmotif of your signature, connecting different eras, and if so, which other components of your current work do you see as a bridge to your earlier work?

The clarinet was the first instrument I truly focused on after starting to play and study folk and classical guitar. After the clarinet, I studied harmony and piano, but the clarinet has remained a constant throughout time, despite some breaks that I always overcame by picking it up again in various contexts. In a way, I consider it a leitmotif of my style—a common thread connecting the different phases of my musical journey.

Was the music scene you were involved in at the time generally very international? Even back then, there were some cross-regional splits and collaborations. I’m thinking of Fra Lippo Lippi and Steven Brown of Tuxedomoon and quite some more.

Since the very first release, a 7″ split for Industrie Discografiche Lacerba included with the Free fanzine in 1985 (Sect. Two), featuring an elaborate package with numbered copies, with the Norwegian band Fra Lippo Lippi with “Leaving” on one side and Minox on the other with “Suite Maniacal”, we have often collaborated with international artists. Later, Steven Brown’s artistic production on Minox’s first album, “Lazare”, then with Luc Van Lieshout, trumpet player of Tuxedomoon, on the EP “Plaza, and again the collaboration between Minox and Lydia Lunch on the EP “U-Turn”, as well as a featuring on the album Downworks with Blaine Reininger from Tuxedomoon. In the 1990s, there were remixes by Murcof, Daedalus, and The Gentle People from the album Nemoretum Sonata of my project Technophonic Chamber Orchestra, co-founded with some Italian collaborators. Finally, the latest productions from my new label Undogmatisch with Lukasz Trzcinski, Ernesto Tomasini, Steven Brown, Nikolas Klau, Paganland, and Sainkho Namtchylak.

The recording of “Lazare” seems to have been an early creative high point. What do you remember most about this intense period?

“Lazare” was our first album, produced for Industrie Discografiche Lacerba, with whom we collaborated on other projects thanks to our connection with Paolo Cesaretti, the label’s founder, along with Lapo Belmestieri who excellently handled the artwork. We began recording in 1985, an intense and exciting period filled with new inspirations and unforgettable sensations. The album was mixed in Brussels by Gilles Martin at Daylight Studio and released in 1986. Unfortunately, its release coincided with a tragic event: the death of two band members, Enrico Faggioli (bass player) and Raffaello Banci (synth player), in a car accident while heading to rehearsal. Thus, our official debut was marked by a period of mourning and withdrawal from the scene for quite some time. After two years, we returned to the stage, but much had changed.

In what aspects do you see the greatest continuities, but perhaps also the key differences, between these early works and your current projects?

The most noticeable differences from my early works are mainly in the 1990s productions with projects like Technophonic Chamber Orchestra and 4Dkiller. However, in the last decade, I have felt a sort of return to my roots, reconnecting in some ways with my beginnings, although developing certain sounds differently across various releases. For example, a certain type of ambient sound was explored in the album “Cronovisione Italiana” under the name Carlo Domenico Valyum and in “Lumiraum” with Lukasz, blending elements of psychedelic improvisation. Naturally, my approach to composition has evolved over time, as has the sound itself, and albums like “Madame E.” and “Zarathustra – Der Grosse Mittag” surely embody a synthesis of everything I have developed throughout these years. Mit wem aus früheren Zeiten arbeitest du bis heute zusammen?

Mit wem aus früheren Zeiten arbeitest du bis heute zusammen?

Apart from Andrea de Witt, who was already involved in the Technophonic Chamber Orchestra, your dub project from around 2000, and Steven Brown, are there other companions from earlier years with whom you are in close contact and exchange today?

The collaborators you mentioned are definitely my preferred partners, along with Luc Van Lieshout and Nikolas Klau. In recent years, especially in Berlin, I’ve been fortunate to meet new artists and friends with whom I’ve built genuine friendships and with whom I plan to continue collaborating. Among them are Ken Karter, who also handles the mastering of Undogmatisch releases, Retina.it, Lukasz Trzcinski, and AUR-OIO, whom I involved in the “Magnum Opus Collectio Series” as well as in the upcoming remix album of “Madame E.”, set to be released soon. This latter project was created a few years ago with the valuable contribution of opera singer Ernesto Tomasini, based on the text from Georges Bataille’s short story “Madame Edwarda”. Additionally, I have been collaborating with Sainkho Namtchylak for several years, with whom I also hope to maintain a friendship.

You’re giving more concerts again at the moment – what projects are you pursuing at the moment?

I’m currently performing a new solo show titled “Suite for Clarinet and Square Wave Generator.” I had been thinking about something like this for a long time, and composing these nine pieces that I’ve been performing live over the past few months came very naturally, almost easily. It’s a very fresh project, created spontaneously, and it hasn’t yet been recorded or released as an album.

Additionally, I’m finalizing and awaiting the release of several new collaborations on three albums in total: the new album by Technophonic Chamber Orchestra, titled “Sanatorium”; the second Lumiraum album with Lukasz Trzcinski; and the remix of “Madame E.” with international guests and friends.

Interview: U.S. & A.Kaudaht

Cover Foto: Kiril Bikov

@ Bandcamp | YouTube | Soundcloud | Instagram | Facebook