As you said earlier, you developed your obsession with British colonialism and militaria already as a boy. When did you start drawing and painting these things, and how early did you develop your critical and satirical approach to the subject matter?

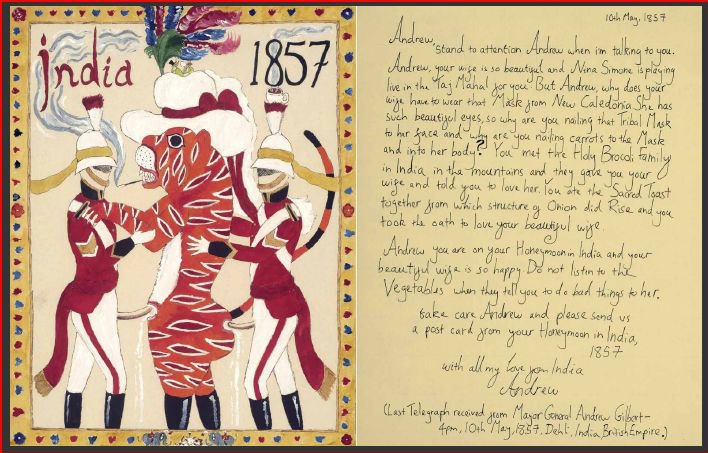

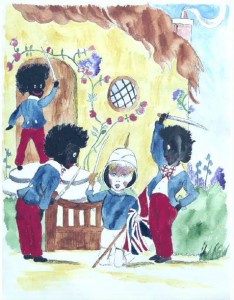

Mililtary history is the first subject I can remember drawing. I estimate aged four. Very early I became obsessed by the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745 and then after seeing the film ‘ZULU’ with the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. As a child I drew the combatants as fruit and vegetables – for example light skinned green grapes for the British and dark skinned purple grapes for the Zulus. As child I remember knowing that the Memorial Service on the 11th day,11th hour and 11th month was absurd. School children stood around a giant phallus dressed in military uniforms. I watched a large amount of Monty Python as a child who frequently parody the British Army. I drew kneeling on the floor in silence, as I still work today. When I was 12 years old they invaded Iraq for the first time, and I knew this was a crime and Shaka Zulu became a role model. The Nina Simone version of ‘Strange Fruit’ had a strong influence when I was very young – she still appears in my drawings today.

Mililtary history is the first subject I can remember drawing. I estimate aged four. Very early I became obsessed by the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745 and then after seeing the film ‘ZULU’ with the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. As a child I drew the combatants as fruit and vegetables – for example light skinned green grapes for the British and dark skinned purple grapes for the Zulus. As child I remember knowing that the Memorial Service on the 11th day,11th hour and 11th month was absurd. School children stood around a giant phallus dressed in military uniforms. I watched a large amount of Monty Python as a child who frequently parody the British Army. I drew kneeling on the floor in silence, as I still work today. When I was 12 years old they invaded Iraq for the first time, and I knew this was a crime and Shaka Zulu became a role model. The Nina Simone version of ‘Strange Fruit’ had a strong influence when I was very young – she still appears in my drawings today.

Is it still a bit like playing with toy soldiers and guns when you paint these historical scenes and put your alter ego character in them?

Once you become obsessed by massed ranks of soldiers you are obsessed for life. But at the same time it is impossible to retain the level of fantasy required that transforms living room carpets in to Gettysburg, for example. However, yesterday I drew some Highland soldiers from the Jacobite Rebellion, I had not drawn them since childhood and I got the same sensation I did then when I painted them now. Such a feeling is impossible to describe. When I have to go to a supermarket I often imagine I am leading infantry in to musket fire, especially while waiting at traffic lights as if waiting to give the order to advance. I like to imagine my head being blown off by grape shot. Once in the supermarket I walk up and down the aisles blessing the products as I if I was inspecting my regiments before the Great Attack. Also, my alter ego never featured in my miniature battles, in this my role was that of God, I looked down from above the imaginary clouds of artillery smoke, in my drawings I do feature, mostly as a yellow bird, but as Creator of these landscapes and controller of these events my powers are also absolute.

You once said that your works are about a certain feeling that you have when you visit European museums. How would you describe this feeling and your reaction to it?

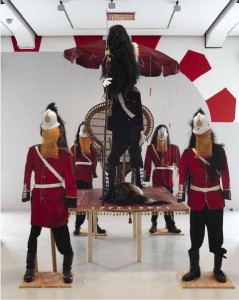

I think I was referring to the sensation I get in Military Museums but also in Ethnographic Museums. The Tribal artefacts and the Military costumes are displayed in a similar setting, so this connects to the emotive environment but also to the absolute excitement caused by seeing these objects. I constantly try to combine these two places in my installations . Again this is impossible to describe, but it is also caused by seeing certain paintings or drawings in museums of Western Art, such as the German Expressionists (Die Bruecke), I become sick and cannot stay long, I must draw. The power of these objects is so great. Picasso described such a sensation when he discovered ‘Primitive’ sculpture in Paris. But I must emphasise I like to parody this also. The German Expressionists, such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner also had an extremely romantic view of tribal art and life, while at the same time they were rejecting the values of their contemporary society and industrialisation . I made, for example in 2008, a large installation outside on the Island of Ruegen of me and Emil Nolde painting a naked African Lady in nature. Both Nolde and i were represented as life size figures wearing British Colonial Military uniforms standing behind eisels and painting. However, I also built Soldier bodyguards in case we were attacked by savages or wild animals. The experience of the Primitive as safe and enjoyable experience, a sun umbrella protected us and we were served light refreshments while we painted. Like in the old ‘Colonial/World Exhibitions’ where villages and natives were put on display for 19th century European audiences. You must realise I have been working with this subject since art college/university, which I joined at 17. So this obsession is constant and this level of inspiration that still drives my mind forward everyday, I draw everyday, cannot be described in rational normal language.

I think I was referring to the sensation I get in Military Museums but also in Ethnographic Museums. The Tribal artefacts and the Military costumes are displayed in a similar setting, so this connects to the emotive environment but also to the absolute excitement caused by seeing these objects. I constantly try to combine these two places in my installations . Again this is impossible to describe, but it is also caused by seeing certain paintings or drawings in museums of Western Art, such as the German Expressionists (Die Bruecke), I become sick and cannot stay long, I must draw. The power of these objects is so great. Picasso described such a sensation when he discovered ‘Primitive’ sculpture in Paris. But I must emphasise I like to parody this also. The German Expressionists, such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner also had an extremely romantic view of tribal art and life, while at the same time they were rejecting the values of their contemporary society and industrialisation . I made, for example in 2008, a large installation outside on the Island of Ruegen of me and Emil Nolde painting a naked African Lady in nature. Both Nolde and i were represented as life size figures wearing British Colonial Military uniforms standing behind eisels and painting. However, I also built Soldier bodyguards in case we were attacked by savages or wild animals. The experience of the Primitive as safe and enjoyable experience, a sun umbrella protected us and we were served light refreshments while we painted. Like in the old ‘Colonial/World Exhibitions’ where villages and natives were put on display for 19th century European audiences. You must realise I have been working with this subject since art college/university, which I joined at 17. So this obsession is constant and this level of inspiration that still drives my mind forward everyday, I draw everyday, cannot be described in rational normal language.

Was there a certain experience which brought you to the opinion that a lot of mainstream views on colonialism and colonial wars are lacking in some way?

As I just described, this work is constant and absolute, I cannot pin point one specific moment or experience. But let us look at the 1964 film ‘ZULU’ as an example. This film inspired many of the leading British experts on the Anglo-Zulu War, such as Ian Knight (author of many excellent books on this subject). ‘ZULU’, directed by Cy Endfield, is a Classic British War Film, of which there are many, unlike in Germany for obvious reasons. So this film is often shown on Sunday afternoons or at Christmas when the British family gathers around the television. It tells the story of the Defence of Rorke’s Drift, where 100 British soldiers defeated an army of 4000 Zulu warriors. As in the American equivalent ‘The Alamo’ most of the film is the build up to the battle itself, waiting for the terrifying Zulu army to arrive, in reality the attack on Rorke’s Drift came directly after the battle of Isandlwana, the Zulu force was tired and ill disciplined, there were not 4 days waiting with dramatic music when the Zulu army finally appears on the crest of the hill (an excellent moment in the film).

The film does not explain why the Zulus are defending their land against British invasion. The film ends with a song about glory, bravery and respecting your enemy, not with the wounded Zulus being shot through the head or put to death with bayonets. One British soldier described the horror of seeing a dead Zulu shot through the forehead, when he turned his body over the whole of the back of his head was blown away, in the film Zulus fall down with no blood at all. The film ends with the list of men who received the Victoria Cross medal, the most awarded in a single day in the history of the British army and again excellent dramatic music.

The film does not explain why the Zulus are defending their land against British invasion. The film ends with a song about glory, bravery and respecting your enemy, not with the wounded Zulus being shot through the head or put to death with bayonets. One British soldier described the horror of seeing a dead Zulu shot through the forehead, when he turned his body over the whole of the back of his head was blown away, in the film Zulus fall down with no blood at all. The film ends with the list of men who received the Victoria Cross medal, the most awarded in a single day in the history of the British army and again excellent dramatic music.

However, through the character of Michael Caine playing Lt.Bromhead, the hierarchy of the British army, its arrogance and the triumph of social class over ability is criticised. At one point a private soldier questions why he is killing Zulus, he never saw one in his village in Wales, why should they be his enemy. The Zulu final attack, which meets rank after rank of British Martini fast loading rifle fire, again an incredible scene, shows piles and piles of Zulu corpses and wounded, twitching and jerking beneath the feet of the British lines and finally Lt Bromhead is disgusted by the violence (at the start of the film he refers to the great Military tradition of the men in his family). Furthermore, the film was banned by Apartheid South Africa, due to fears of rising Zulu nationalism. The contemporary Zulu leader Buthelezi played the historical Zulu King Cetshwayo kaMpande.

You must understand one could write 6000 pages about the significance of the film ‘ZULU’, it represents something naïve yet pure, perhaps British culture before it was destroyed by  American influence and corrupted by a deep modern cynicism that attacks everything and offers nothing. It represents ridiculous patriotism and propaganda,it represents technology against primitivism (I gave Ernst Ludwig Kirchner a copy of the DVD) it represents the troubled life of the producer and actor Stanley Baker. I leave the fim ‘ZULU’ with a quote from a history of the British army published in 2009 – “the desperate fight at Rorke’s Drift in 1879 underpinned the heroism of the airborne forces at Arnhem in 1944, and continues to do so in Afghanistan’…

American influence and corrupted by a deep modern cynicism that attacks everything and offers nothing. It represents ridiculous patriotism and propaganda,it represents technology against primitivism (I gave Ernst Ludwig Kirchner a copy of the DVD) it represents the troubled life of the producer and actor Stanley Baker. I leave the fim ‘ZULU’ with a quote from a history of the British army published in 2009 – “the desperate fight at Rorke’s Drift in 1879 underpinned the heroism of the airborne forces at Arnhem in 1944, and continues to do so in Afghanistan’…

May I also point out that small numbers of England football supporters travelled to the World Cup in South Africa in Replica White Helmets of the Zulu War, before their complete destruction by Germany.

What role does the work of Kipling play for you? In his most (in)famous poem the colonized are described as “half-devil and half-child” and thus it is the “white man’s burden” to “serve [their] captives’ need”. Do you think the tension between some kind of misguided idealism and chauvinism may be of relevance for your art?

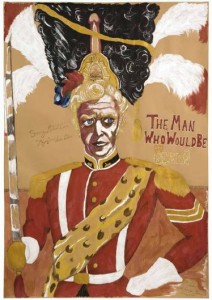

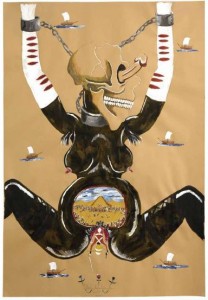

That is an excellent quote, thank you! Mr Kipling, or Edwina as we used to call him in the Camp tent, has inspired me with his poem ‘A Young British Soldier’ especially the line about better to shoot your self than be mutilated by the Afghans-which is of great significance to today. His book ‘The man who would be King’ is the inspiration for many of my drawings and for my own book ‘The man who would be Queen’ (my 19th century autobiography). Again you ask me to explain something psychological and emotional in rational words. I use the symbol of the white phallus to represent the European Colonial powers. I also use the Medieval Christian symbol of Jerusalem as a Sacred Female figure and like to link this to Ulundi, the Zulu Capital destroyed by the British in 1879. The militant imagery of the Christian missionary, the Medieval Crusade visual propaganda such as the sculptures of Vezelay (where Pope Urban II preached the first Crusade) also connect to the British Colonial military campaigns. The fact that the Europeans burned African idols, while the Protestants destroyed the Catholic idols is also greatly inspiring. There is also a British propaganda against Germany from the First Great War, that describes German War Memorials which were covered in Nails, like African Fetish, and therefore the imagined primitive dark rituals of the German people, as negative propaganda. The worship of the object in contemporary European society, the Traffic Light as an idol covered in Carrots, relates also to the idea of the arrogance of European society in its view as being enlightened or civilised, as you describe.

In some of your works, you decidedly mix accessoires of the colonizers and the colonized with each other and thus create interesting hybrid figures (a Zulu warrior with the Union Jack on his shield or mixed media soldiers with a native look, for instance). Do you think that this sort of „positive“ intercultural influence between groups is something that falls short when we regard these historical events solely as encounters of contrasting cultures?

In some of your works, you decidedly mix accessoires of the colonizers and the colonized with each other and thus create interesting hybrid figures (a Zulu warrior with the Union Jack on his shield or mixed media soldiers with a native look, for instance). Do you think that this sort of „positive“ intercultural influence between groups is something that falls short when we regard these historical events solely as encounters of contrasting cultures?

I like to draw Zulu female warriors wearing the British Phallic symbol, the White Helmet. I also like to design my own uniforms for my African Elite Bodyguard. I am inspired by photos of African leaders who adopt European 19th century military uniforms and this language of power and propaganda and combine it with indigenous power symbols. Idi Amin’s regiments in British/Scottish uniforms are fascinating. Furthermore, I see a strong similarity between the uniforms of the 19th Century European Tribes, with their feathers, leopard and bear skins, the way they are presented in museums, in glass cases, in darkly lit rooms, to African and Oceanic Tribal Art and to the Zulu military uniform – with their feathers and animal skins. I must point out that the Shaka Zulu is often compared to Napoleon as a great reformer of the military and a great strategic leader. His regiments could be distinguished by different feathers and coloured cow skin shields. He introduced military service and a system of barracks, he shortened the spear for stabbing (like the Romans), he rejected the ceremonial battle (throwing spears and insults) in favour of total annihilation of the enemy , he removed the sandles so his troops could run faster. He developed the formation ‘The Horns of the Buffalo’ (described by the Boer character in the film ‘ZULU’ – using a sword he carves a diagram of this into the sand and used at the Battle of Isandlwana and complete destruction of the British Regiments). Shaka Zulu did to South Africa what the British were doing to the world, he conquered and subjugated all those around. Like many European leaders his absolute power lead to his insanity, and he was assassinated by his own people. I like to compare him to MacBeth, and it is not a coincidence that Shakespeare and Shaka Spear are the same. The role of the Witchdoctors and their political influence on the Zulu court is well documented, like the Witches in MacBeth. The life of Shaka Zulu mirrors the Christian Mythology as well as the European Mythology such as Excalibur and the Spear of Shaka Zulu.

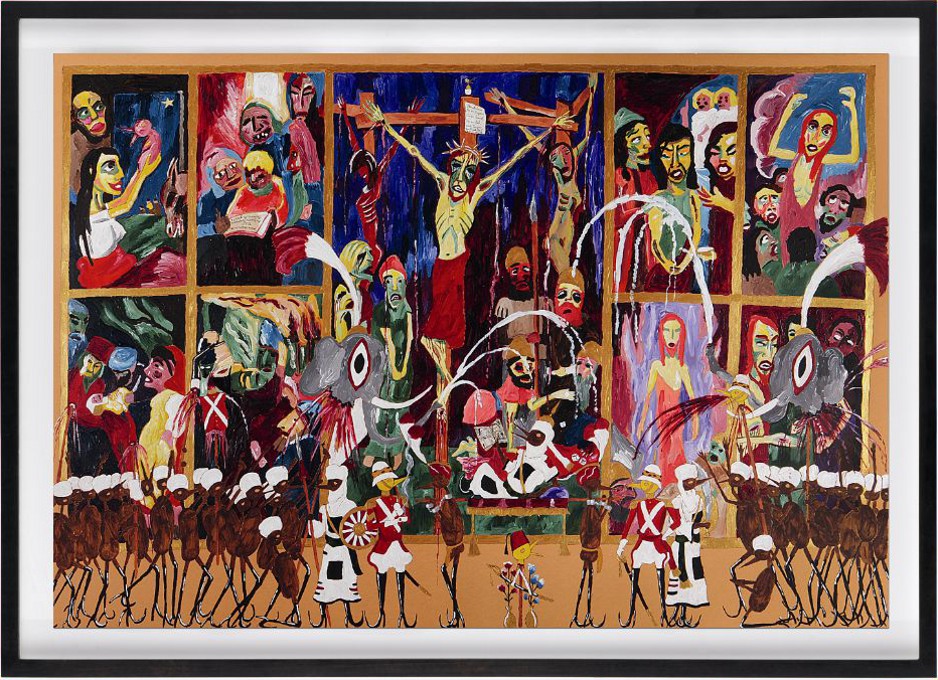

A final example of this cross over in my work would be the solo exhibition ‘Trophies of the Savages’ (Gallery 207, Prague in 2012). The Title of the exhibition comes from a painting by Emil Nolde. Nolde travelled with the German Colonial Expidition in 1913/14 to the South Sea Islands. The painting ‘Trophies of the Savages’ depicts severed heads in a jungle, referring to the head hunting practice of the natives. I used this image and title however to refer to the German occupation of Namibia and the severed heads taken as part of scientific research. So the term savage is then imposed on the European powers. Furthermore the main image of the exhibition was based on a Crucifxion painting my Nolde, the title ‘Trophies of the Savages’ therefore also refers to the European Idols of Christian worship, and as in my drawings the primitives are the Royal Family with their deranged rituals rather than exotic natives.

A final example of this cross over in my work would be the solo exhibition ‘Trophies of the Savages’ (Gallery 207, Prague in 2012). The Title of the exhibition comes from a painting by Emil Nolde. Nolde travelled with the German Colonial Expidition in 1913/14 to the South Sea Islands. The painting ‘Trophies of the Savages’ depicts severed heads in a jungle, referring to the head hunting practice of the natives. I used this image and title however to refer to the German occupation of Namibia and the severed heads taken as part of scientific research. So the term savage is then imposed on the European powers. Furthermore the main image of the exhibition was based on a Crucifxion painting my Nolde, the title ‘Trophies of the Savages’ therefore also refers to the European Idols of Christian worship, and as in my drawings the primitives are the Royal Family with their deranged rituals rather than exotic natives.

In academic cultural studies, a critical approach to colonialism and Britishness seems quite trendy – one of many „post“-whatever phenomena, whose intellectual depth is sometimes doubtful… Are you interested in such things and is there a book that you recommend?

I am not interested in such things, but I recommend the short documentary film ‘The Mad Masters’ / ‘Les maitres fous’, 1955, by Jean Rouch. I saw this film recently and it confirms a number of my visions.

Where do you draw most of your inspirations from when it comes to particular details? Are there certain documents or artefacts that strongly affect some of your works?

I constantly search for historical material and visit museums. For British Empire military history I recommend the books by Ian Knight and Saul David. Also the Osprey series (available in Berlin at Berliner Zinnfiguren shop in Charlotenburg). The new Book ‘Human Zoos – The invention of the Savage’ (published 2012 by Musee du Quai Branly, Paris) contains excellent historical photos and illustrations. I was given the book ‘Kolonialpiraten’ Franz Rose (1941 Berlin) by the Berlin-based artist from Stralsund Stefan Pfeiffer, which contains superb anti Empire illustrations, including a reproduction of the painting of the execution of Indian Mutineers, tied to the fronts of cannons by the British. The Ethnographic Museum in Berlin Dahlem and the Tervuren Africa Museum Brussels must be visited. For devotees of Primitvism Heidelberg is an epicentre of Ancient Energy.. The Ethnographic Museum in Heidelberg is incredible and one can then walk to the Prinzhorn Collection Musuem and see the carved wooden sculptues of Karl Brendel including ‘Militarism’ which are permanently displayed next to the Kota reliquary figure that Hans Prinzhorn used in his comparisons to illustrate his theory of Primitivism. Also nearby is the Museum HausCajeth for Primitive Painting.

Returning to film – I watch often ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’ (1968) which contains animation sequences depicting the British Empire and Army. Also the film we discussed already ‘Soldier Blue’ (1970) in which the American Cavalry commander wears a white British Colonial Helmet while massacring a village.

The Biography of Shaka Zulu must be read. After the death of his mother, Shaka made sex illegal for one year as a form of national mourning. To test the allegiance of his regiments he made them line up and had young naked Zulu women dance in front them, any man whose spear rose toward the sun (became sexually aroused) had his head smashed in with a club.

The Biography of Shaka Zulu must be read. After the death of his mother, Shaka made sex illegal for one year as a form of national mourning. To test the allegiance of his regiments he made them line up and had young naked Zulu women dance in front them, any man whose spear rose toward the sun (became sexually aroused) had his head smashed in with a club.

Your book „Andrew Emperor of Africa“ is a visual narrative with an alter ego of yours as the protagonist. How would you introduce and describe this other Andrew Gilbert character?

I try to keep this short. Firstly he is an Officer, he is left alone in an outpost in Southern Africa, at this point through isolation and malaria he begins to hallucinate an entire Empire which he rules. He begins to build life size soldiers, his regiments and companions from wood and painted uniforms and cabbages (for their heads and breasts) as well as his servants. He makes drawings that he believes are photos of all his past glories. By coincidence there was a Major General Andrew Gilbert of the Black Watch Highland regiment. He was wounded in the Sudan and killed in South Africa fighting the Boers in 1899.

The narrative is not constant, I move around different times and campaigns. Therefore I can meet different historical figures – such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, The Mahdi of the Sudan or General Gordon of Khartoum, who also drew flowers and whose head was cut off when Khartoum was captured by the Mahdi’s army. I also met the Holy Brocoli who is my spiritual protector, but also prone to extreme violence.

I have many wives, all of whom are executed for specific crimes such as chopping the sacred onions or burning the toast, or because they like the work of another artist more than mine.

There is this case – the Lady Rajbaj picture – where Andrew Gilbert appears as a military officer and as a painter in one image. To avoid a term like ”meta artistic“, do such gimmicks just exist for the fun of confusion, or do they also show a bit more about your role as an experiencing and a (re)producing person?

There is this case – the Lady Rajbaj picture – where Andrew Gilbert appears as a military officer and as a painter in one image. To avoid a term like ”meta artistic“, do such gimmicks just exist for the fun of confusion, or do they also show a bit more about your role as an experiencing and a (re)producing person?

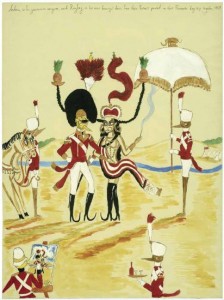

Certainly not for confusion, in this drawing I represent myself in two of my roles, as a General, and a military artist whose job it Is to record the important events – as God’s Witness, his eyes on earth. It is common in art history to see artists paint themselves hidden in important events. In the unpublished drawing of the assassination of Kennedy, I appear in the car, with my slaves chained to the back of the car on my military procession and I appear at the window, shooting my own head off.

By the way Lady RajBaj was inspired by a drawing of the historical figure Lakshmi Bai, the Rani of Jhansi, a leader against the British in the Indian Mutiny. I found a drawing of her in the Saul David book ‘The India Mutiny’ and became obsessed by her beauty.

Many of your pictures are very brutal, and often the more cartoonish they are, the more pornographic they become. Apart from the fact that they are also very amusing, who do you think deserves mostly to be shocked by this historiography drenched with sex and violence?

The violence I draw because I need to. Because it helps me stay calm and because of contemporary events which make me angry. There is an enemy that thinks it is normal to kill for wealth and power. This enemy should taste the soup of justice, 10 000 prawns, 20 000 sacred onions and many monks teeth and the skulls of 10 000 Owls go into this soup.

Thinking of the topics of your work I was wondering to what extent Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness” and/or Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now” may have influenced/inspired you.

I was told to read ‘Heart of Darkness’ by a professor at art school, she saw a link between my primitive idols of European culture and violent rituals and this book. The book is very good. I often draw Helicopters in the 19th century blowing up civilians inspired by the scene in this film.

I constantly imagine a clearing in a forest, where my idols stand, lost rituals of violence and vegetable blessing took place there, I stumble across these idols by chance when I leave the outpost, the blood is fresh, the ritual could have been 1000 years ago, or that morning. This idea excites me and I am the only one except the High Priest who can read the language written in violent mark making and chopped Mushrooms. The heads on spikes everywhere in “Apocalypse Now” are also inspiring.

To leave contemporary reality as Kurt does and the character in Heart of Darkness, is a great inspiration, the colonial landscape is never ending, the campaigns never end, the jungle never ends, the imagination never ends.

There is a photo of you, in which you stand in a solemn military pose in front of insignia like a flag and uniform parts. For me, this has something parodistic as well as serious at the first glance. When you deal with the average British soldier from colonial history, which aspects are interesting for you in a positive and empathic way?

There is a photo of you, in which you stand in a solemn military pose in front of insignia like a flag and uniform parts. For me, this has something parodistic as well as serious at the first glance. When you deal with the average British soldier from colonial history, which aspects are interesting for you in a positive and empathic way?

There is a better photo in which I wear a red uniform, with potato sack as mask or veil, and a necklace of carrots. The veil refers to Tribal Ritual costume and the Veil in Perisan Miniature painting. As you say a parody of the patriotic pose, but also something else, connecting to visual reprentations of power, it was the image used for the 2009 exhibition Invitation Card ‘The Zulu Queen stood as Jerusalem fell’ at Gallery Ten Haaf Projects, in Amsterdam.

There is a small monument to the British Commandoes in the Highlands of Scotland. They trained there in the Second World War. Today are tributes to the Commandoes killed now in Afghanistan. By chance I visited this site while preparing the exhibition ‘Andrew’s death in Afghanistan,1842’(Power Gallery, Hamburg 2009). It is not the fault of the individual soldiers sent to these countries to die, but it is to be expected that people will defend their land against foreign occupation. My Victorian soldiers drink Coffee in their tents, attend Lonnie Donegan concerts to increase their Moral on their over seas Campaigns, are killed and carry out atrocities upon the civilian populations they are meant to be liberating in the name of Civilisation.

In your book you sometimes show the brutality of both antagonizing parties in a war with a strange mixture of empathy and sarcasm. In the India chapter for instance, a work like „Smash British Rule in India“ has its equivalent in „Smash Gandhi“. Do you think that your childlike spitefulness is the price that both parties have to pay for having their say?

I am obsessed by the link between propaganda and advertising, and the fact that propaganda of all sides looks the same and functions the same. Also because I draw constantly my mind moves fast and changes depending on how much coffee is drunk or what time of day it is. In the examples you give you will notice the pro British propaganda is much more primitive in its execution, while the pro India image is very fine in its rendering. The famous quote of Ghandi is, when asked “What do you think of European Civilisation” he replied “That would be a good idea”. I draw massacres committed by all sides, in fact the wife I was on my honeymoon with in India, a European woman, was butchered at the hands of the Indian Mutineers at the Cawnpore Massacre (1857), luckily I was watching a game of cricket at the time and I survived – though my team lost.

People tend to be lazy and many seem to prefer happy endings and easy and clear solutions but there is often a certain amount of ambivalence in your work. Have you ever encountered feedback from the audience that was hostile because of this?

People tend to be lazy and many seem to prefer happy endings and easy and clear solutions but there is often a certain amount of ambivalence in your work. Have you ever encountered feedback from the audience that was hostile because of this?

No, occasionally I am warned about romanticising a deranged and brutal dictator like Shaka Zulu.

Do you generally care how (and how well) your work is understood by your audience and the media? What would probably be the most inappropriate feedback you could imagine?

Yes this understanding is very important. And generally it is understood correctly and is greatly appreciated by those who should appreciate it. If the Queen would invite me to be her Royal Artist this might be a problem, or if Bono from U2 became a fan. Or if I was invited to make a recruitment poster for the British army, this would also be a problem.

Recently there were again discussions about what country actually owns the Falkland Islands. Morrissey told an audience in Argentina that the islands “belong to you”. How do you feel about such remnants of a colonial past?

Firstly the Morrissey fans at art college were incredibly arrogant and elitist, but that is not his fault. The British in the Falklands is as ridiculous as the Germans in Namibia was, or as ridiculous as people who worship Parsnips killing people who worship Cauliflowers.

Historical (Meta-)Fiction has been quite popular in the UK since the 80s, think Fowles, Byatt, Ackroyd and other writers. I think that Barry Unsworth’ slave trade novel “Sacred Hunger“ offers an interesting view on certain aspects of colonial history. I wonder if you know it or its sequel “The Quality of Mercy”?

Unfortunately I don’t know these books. The ‘Sacred Hunger’ sounds interesting and I will try to find this. I read almost no fiction anymore, but I need to find a copy of ‘Ape and Essence’ by Aldous Huxley which I read many years ago and need to re read.

Last year you did this Berlin exhibition together with David Tibet. How did it come about and how do you think does the work of both of you fit and correspond to each other? As you told me, you already knew his music group and some of the people contributing to it…

The English artist and friend Lucy Stein gave David Tibet my book ‘Andrew , Emperor of Africa’. He contacted me at the same time I was invited to exhibit at a project room in Berlin called the nationalmusuem. I asked David if he would exhibit with me and he agreed.

The English artist and friend Lucy Stein gave David Tibet my book ‘Andrew , Emperor of Africa’. He contacted me at the same time I was invited to exhibit at a project room in Berlin called the nationalmusuem. I asked David if he would exhibit with me and he agreed.

I think this was an excellent exhibition as many artists in Berlin agreed. David’s Hallucinatory images combined very well with the religous visions I was working on at the time of the Mahdi of the Sudan. David is a very obsessive collector and researcher as I am. You summarised the link between our work very well already in African Paper. I would add to this that I have always been inspired by his lyrics and the repetitive violent screaming he employs, this reminds me of the hammering of nails in to Fetish Objects which explains my fascination also with John Cale (for example the song ‘Fear is a Man’s Best Friend’). His paintings are excellent regardless of whether you know his music, this was also something a lot of Berlin artists agreed with. I need art that releases the certain feeling that we have already discussed and cannot be described, I get this from both his music and his paintings.

I have been listening to Current 93 since I was 16 and still at school and know Michael Cashmore through the artist Steffi Thiel for many years.

You once said in an interview that you “drew, but […] did not invent the image of a baby ripped from the womb”, illustrating that people tend to forget that atrocious crimes are committed in the real world and not necessarily on canvas. When people in Germany talk about horrible crimes etc. they often say that it is “unimaginable” (unvorstellbar). I always think that these crimes happened because it was in fact possible to imagine them. Is your art there to show what others consider to be unimaginable?

If I did not draw then I would not do anything useful, my work keeps me alive. The crimes of the past are repeated over and over, the technology for killing civilians has advanced but the crimes and motivations for these crimes are the same. I draw for myself, firstly, to try to understand these things, also because I love to draw uniforms. Because I love to research history and I love to leave contemporary reality. But at the same time as I hope it is clear in this interview the work relates to contemporary problems. I see no difference between a television and a microwave filled with old potatoes. There is a grey veil of mediocrity being drawn over everything, through advertising, through media, it is vital to expose the beast behind this veil, to show the absolute violence hidden behind the celebrity dance programmes. The Primitivist artist Dubuffet said it is better to eat burnt Broccoli and to experience something real rather than bland, while Thomas a Kempis the Middle -ages Mystic preferred to listen to the sound of frogs croak than to the banal pleasant tunes of the church organ. The Holy Brocoli comes in peace, but when his children are time and time again murdered he will take up the Machete of Justice and drive it deep it in to the head of the beast.

(M.G., T.M., U.S.)

New Works:

“Andrew And Nolde Meet The Mahdi, 1885″

Year: 2011

Format: 70x100cm

Watercolour, acrylic and pen on paper

Private collection Duesseldorf

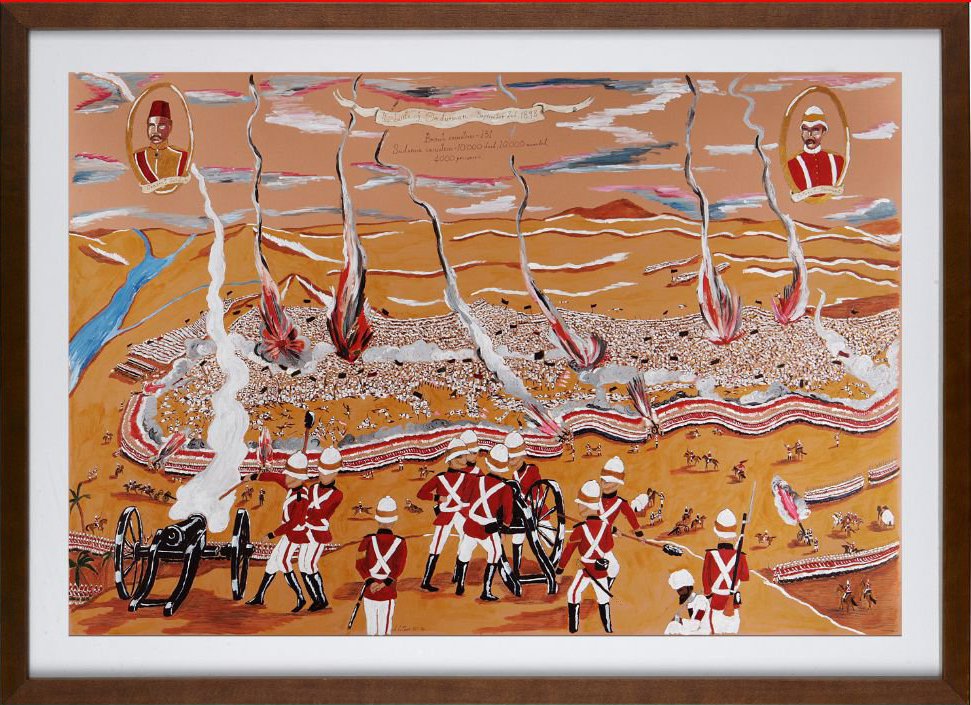

“The Battle Of Omdurman, 1898″

Year: 2012

Format: 70x100cm

Watercolour, acrylic and pen on paper

Courtesy Power Galerie (Hamburg)

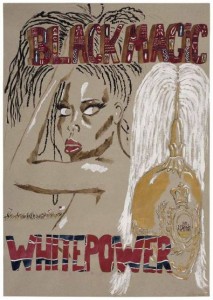

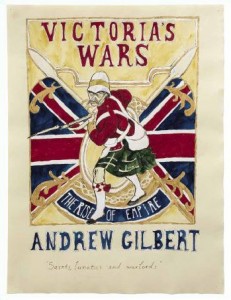

Older titles are: The Man Who Would Be Queen, The Birth Of Andrew Emperor Of Africa, Black Magic White Power, Africa 1879, Victoria’s Wars, Andrew And Lady Rajbaj, India 1857, The Defense Of Jerusalem, Monument To Andrew The Zulu Queen (Andrew Gilbert: Andrew, Emperor of Africa. Bielefeld: Christof Kerber 2011)